“What is ‘My Romantic Ideal’? If there were just one, I’d have been able to stop making images searching around the borders of yearning, imagining, and lusting, many years ago. These are some recent attempts at mapping those.” – Robert Flynt

Robert Flynt. Untitled (NPCG; NYC 41), 2023 Unique inkjet photograph on found atlas page (additional image on verso) 11 x 16 inches

text by Summer Bowie

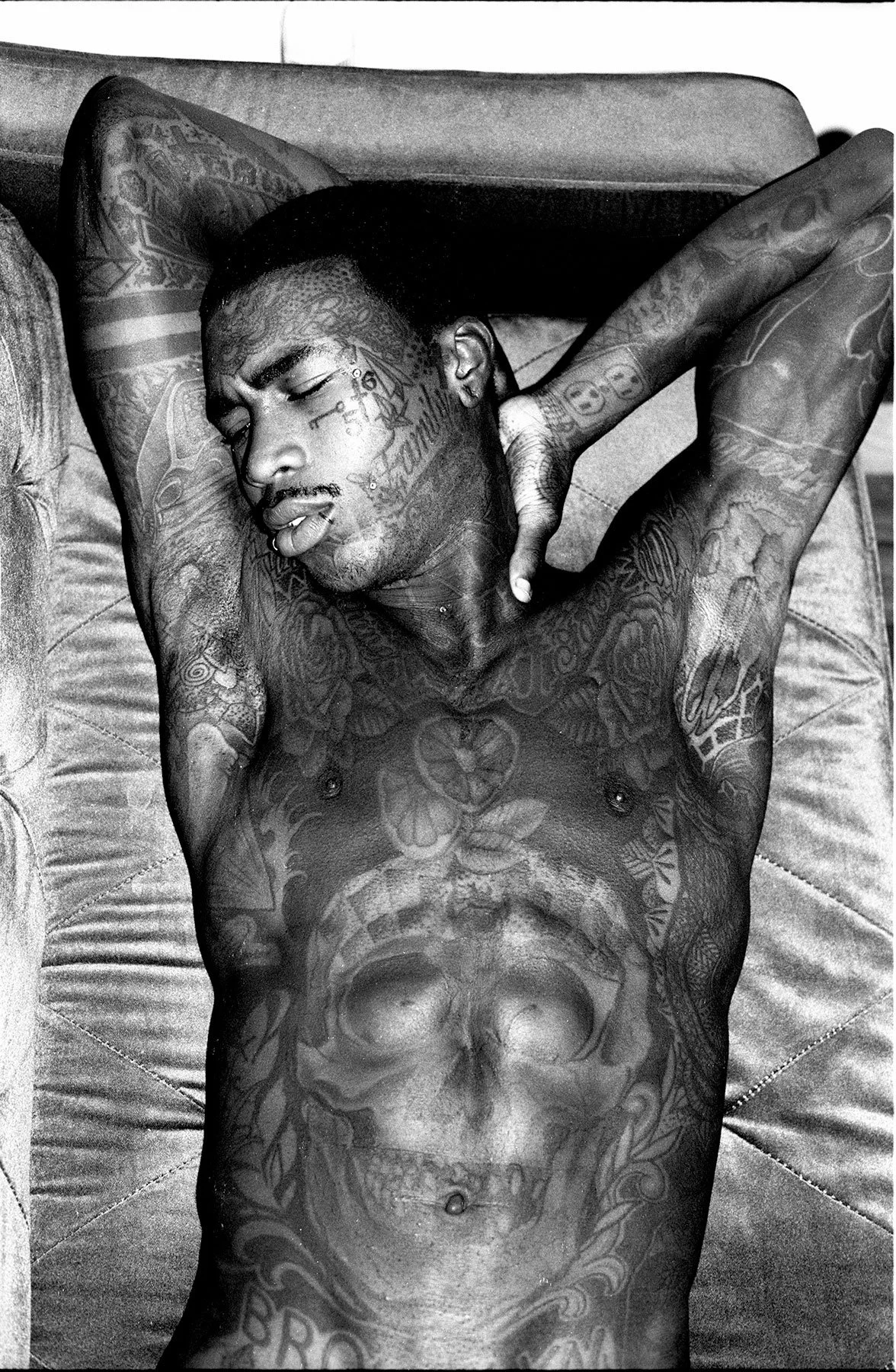

Like Lee Oscar Lawrie’s sedulously brawny statue of Atlas lunging interminably under the weight of the world in Rockefeller Center, Slava Mogutin has taken on the ambitious charge of defining Queer romance in all of its variegated multitudes. Drawing from the work of twenty-eight artists, his curation coalesces into a comprehensive cohort across the generational and gender spectrums with searingly vulnerable takes on romanticism. Such an endeavor seems only natural considering Mogutin’s personal history of putting himself on the line for the sake of his community. Working in a plurality of media, he has always questioned and prodded the boundaries of sexual freedom, from his early Queer activism and writings for the political weekly newspaper Novy Vzglyad to being the first person to register for a same-sex marriage in Russian history with his then-partner, Robert Filippini. As the first Russian citizen to be granted exile in the United States for reasons of homophobic persecution, his commitment through legal and artistic means to broaden our understanding of love and its ultimate liberation remains steadfastly on the frontlines.

In Mogutin’s “Stone Face (Brian), NYC” (2015), we see an outstretched arm holding almost identical copies of a photograph containing a man’s face partially buried in rocks. More than just a nod to David Wojnarowicz’s “Untitled (Face in Dirt),” we see lower Manhattan’s skyline at sunset on the horizon. Where Wojnarowicz quietly mourns the violent isolation of ultimate abjection, Mogutin’s figure is rendered in print and then literally held by another man in the city of his exile—a photo taken almost a quarter century after Wojnarowicz’s untimely death from AIDS at just thirty-seven years of age. In Stanley Stellar’s “Cherry Grove Kiss, Fire Island” (1990), the man’s entire face emerges from the sand in anticipation of an impassioned kiss. Where Mogutin trades dirt for pebbles, Stellar trades it for sand, making the burial feel elective and impermanent. Made at a time when the AIDS crisis was still looming large, it effectively sublimates the unthinkable trauma of carrying such an insidious burden into not only erotic, but manifestly romantic pleasure.

Slava Mogutin

Stone Face (Brian), NYC, 2015 Offset print, 20 x 27.5 inches Edition of 10

Stanley Stellar

Cherry Grove Kiss, 1990

Archival analog tinted silver gelatin print

15 x 15 inches, 16 x 20 inches frame

Artist Proof

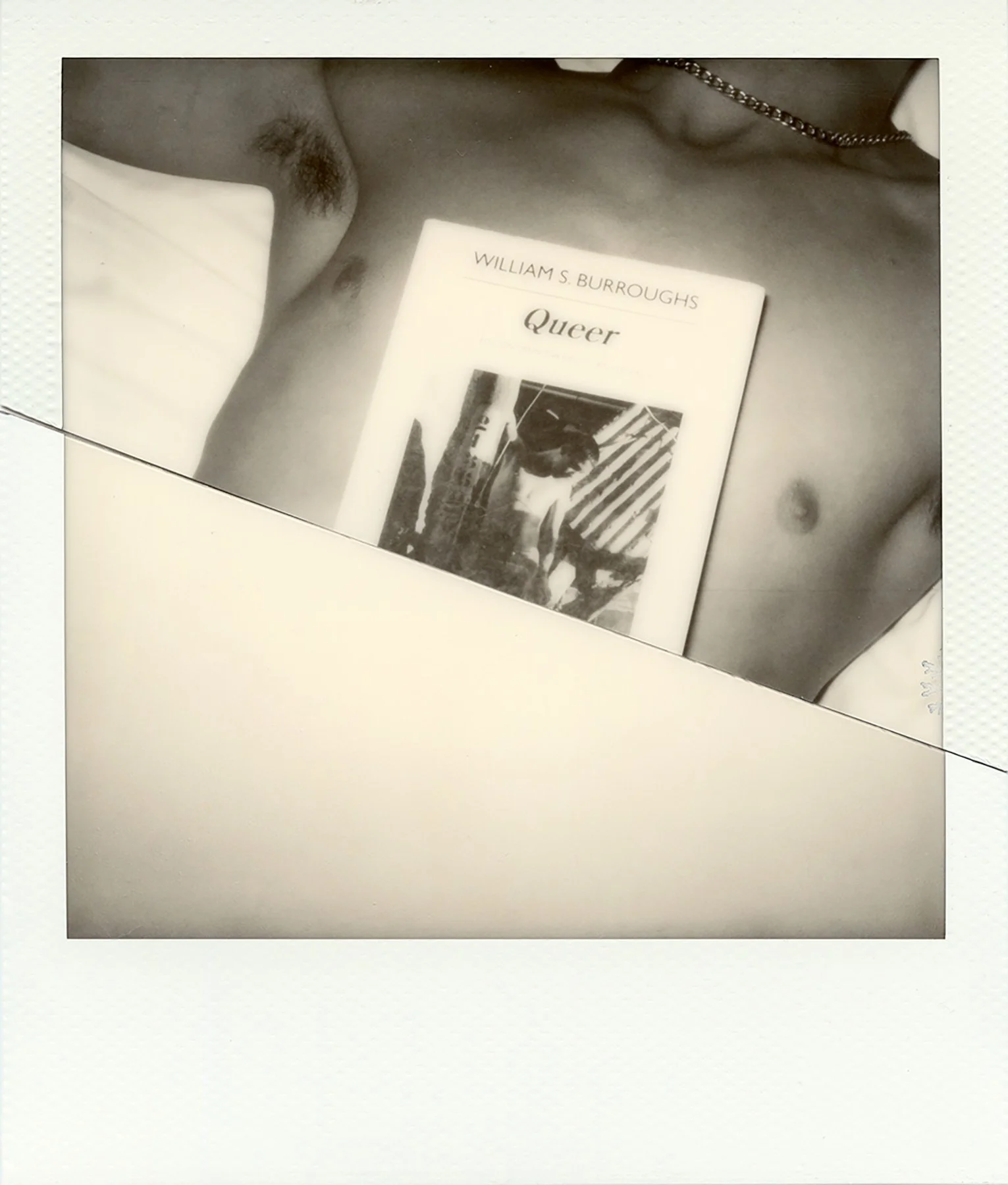

Held both literally and figuratively by the Bureau of General Services—Queer Division, My Romantic Ideal implores us to define romanticism on our own terms, knowing that in the process of queering the heteronormative parameters, we normalize our queerness. He is glitching the hegemonic system, à la Legacy Russell, with an unabashed proposal to reexamine our assumed notions of tenderness, intimacy, and beauty. These images represent a disparate yet equally valid selection of possibilities for romantic encounters, both with others and with self. They are safe spaces that are not safe for work, and at times, I can’t help but blush at the thought of sharing them. Some of them are too risqué even for the press kit, like Quil Lemons’s “Untitled (Penetration)”—which is reason enough to see the show in person if you live in New York. Others, like Carter Peabody’s “Bastian Floating,” lean into dreamy ecosexual escapism with an Adonis-like figure floating in sea grass-lined, turquoise waters. “I have only known shame when it comes to love. For me, romanticism is freedom from heteronormative oppression. The bodies floating in my pieces are unattached to the strict norms of our world and free to feel, explore, and play with the sensuality of the sunlight and water surrounding them. There is an innocence and wonder that takes hold when we become our inner child in search of love, and the judgement of our subconscious just melts away.” Here, romance is imbued in everything surrounding the act of love, rather than in the act itself.

Carter Peabody

Bastian Floating, 2025

C-print on Metallic Paper

23.5 x 31.5 inches

Edition 1/12

Benjamin Frederickson’s “Self-Portrait with Lillies” features the artist sitting nude in a brutalist wooden chair, peering out of a floor-to-ceiling window that reveals a verdant forest. He props his feet on the identical chair facing him with an enormous vase of lilies placed tightly between his legs. If we deign to inquire, we cannot help but notice that he is gently indulging himself with just the tips of two of his fingers. This sensual, autoerotic moment of bliss feels utterly unimpeachable.

Benjamin Frederickson

Self-Portrait with Lillies, 2019

Chromogenic print

15x19 inches image, 16x20 inches sheet

Edition of 3+2APs

Bruce LaBruce’s “Hunk with Sneaker” might be having an autoerotic moment of his own. Then again, he might just be testing that theory about guys with big feet. Berlin-based American photographer Matt Lambert presents us with two new pieces from his forthcoming book If You Can Reach My Heart You Can Keep It. Luridly graphic in content, these images leave us only to imagine what kind of tantric infrared technology he is patenting in his dark room/dungeon. Pierced and penetrating, his figures find themselves interlocked in full coitus with mysteriously luminescent erogenous zones. Berlin-based Spanish photographer Gerardo Vizmanos says, “I have a complicated relationship with the term ‘Romanticism’—I see it as both something we enjoy and something that restricts us … which is why I focus on love and desire instead. They offer a more radical, utopian force—one I strive to capture in my photography.” His dancer performs a preposterously blasé hamstring stretch, his entire body giving rise to the kinds of questions often inspired by an ample-when-flaccid endowment.

Bruce LaBruce

Hunk with Sneaker, 2008

Digital C-print

11 x 14 inches

Edition of 1/5

Gerardo Vizmanos

Dancer, 2024

Archival Pigment Print

8 x 10 inches

Edition of 7

Matt Lambert

Warm Amour, Paris, 2017

Thermal Imaging C-print

20 x 24 inches

Edition 1/5

Of course, no collection of photography on the subject of Queer romance would be complete without the work of Paul Mpagi Sepuya. His intimate studio portraits meditate on the vulnerable interplay of sensuality and performativity between artist and subject—that ineffable power dynamic inherent in every nude portrait since time immemorial. In all of these artists, we see an earnest motion to decouple our fantasies with any notions of shame or fear—to let them not only be conspicuous but copyrighted in our names.

My Romantic Ideal is on view through August 31 @ The Bureau of General Services—Queer Division 208 West 13th Street Room 210, New York